The in-house winter maintenance and vehicle tracking system built by the Public Works Department in Hartford, Connecticut, coped with record snowfalls and cut costs too.

When it comes to dealing with the effects of mother nature, transport agencies can find themselves in a lose-lose situation: criticised if the roads or rail lines are disrupted by snow, ice or floods for more than a few hours and lambasted for wasting money if the equipment and stockpiles put in place for a hard winter remain unused.

Equally, when a storm hits and everything swings into action, the situation is very fluid and keeping abreast of what is happening on the ground is a major challenge. This is especially the case for road authorities who need to know if prioritised roads have been cleared and which still need clearing or re-clearing.

Like many other US cities, Hartford, Connecticut, relied on the local knowledge of the control room staff to know which areas would be the worst affected and the experience of plough operators to know which roads to plough and in what order. The city authority is responsible for clearing more than 320 centreline kilometres (200 centreline miles) of road and more than 42 centreline kilometres (26 centreline miles) of sidewalk. Once its operators had cleared their primary routes they returned to the depot and the duty manager may deploy them on secondary routes without knowing if other primary routes were proving more difficult.

“Like other public agencies we had a subscription to a regional planning agency AVL system which was designed for public safety, so it really wasn’t that intuitive for public works,” says the authority’s GIS project leader Aaron Nash. “The refresh rate on each vehicle was 30 seconds so it was hard to track and monitor the fleet remotely. In 30 seconds they could move to a different block, and the cost was high – around twice per truck per month compared with the cost of our revised system. And we had no control over the data plans, refresh rate or the user interface.”

Furthermore, only 70% of the fleet was instrumented and there were many complaints about roads not being cleared in a timely manner. So when a new, interim director of the Public Works Department was appointed, he set a four hour time limit to clear a road. As Hartford had its own GIS system, the interim director requested Nash devise a system to bring the whole process in-house to combat the lack of on-the-ground knowledge. This would also enable the development of a more suitable user interface and allow the department to control system specifications including the refresh rate.

Nash was made aware that

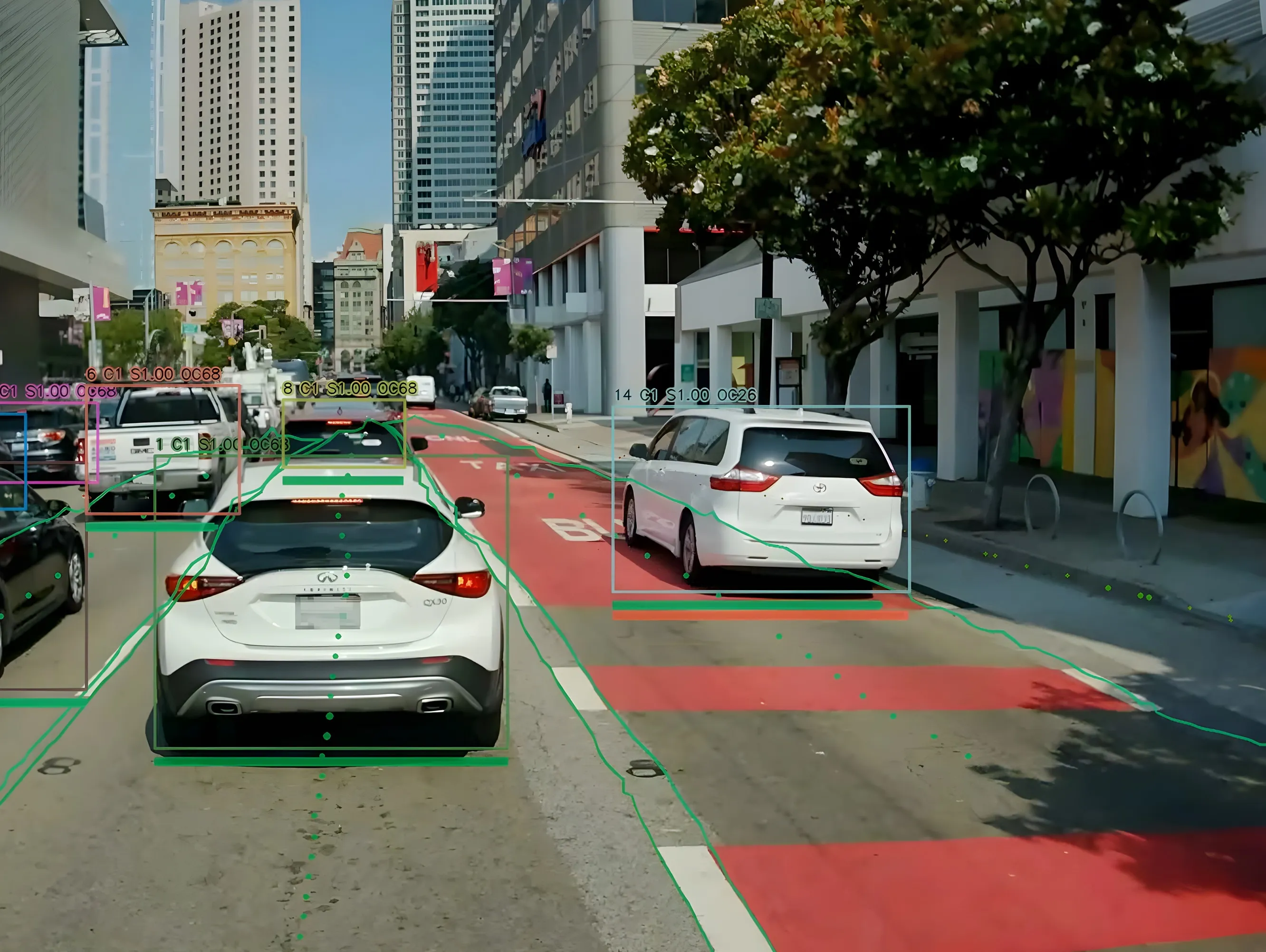

Nash and his team then built a vehicle tracking system with location of each plough plotted using Esri's graphical user interface onto a modified Esri dashboard to visualise their distribution and progress on the ground. “We built our system in one of ESRI’s dashboards (Flexviewer) and a customised widget to track and research vehicle locations – so we can now set our own refresh rate. The plough trucks are updated every three seconds and the refresh rate of the dashboard is five seconds, so there’s a maximum eight second delay. And we have full control of the stored data.”

Using an app on their mobile device the field supervisors can confirm that a satisfactory clearance has been carried out.

Around the same time time, the ploughing operations were also revised. Initially there were 27 routes (11 main and 16 secondary) covered by 21 six-wheel plough trucks and two supervisors. While the roads were all plotted and prioritised for snow clearing, there had been consistency problems as driver were given a different route each day.

Nash: “Drivers never built up experience on the best way to plough those roads so clearing was relatively slow and the level of complaints was high. We should be clearing our neighbourhood routes in four hours, major roads routes are cleared in two as they are shorter in length and drivers plough in tandem on the multi-lane roads.”

The interim director wanted major routes cleared in two hours and the department also needed to keep the downtown area clear and success was to be gauged by the number of complaints received and how many contractors were used.

To achieve this, the city was divided into six management districts each with four routes, four ploughs, four drivers and a supervisor. There were also six prioritised major routes, one in each district, which are not part of the normal driver route. The drivers work on clearing neighbourhood routes until there is accumulation on the major roads, when the supervisors coordinate gathering all the plough trucks to work in tandem to clear the major roads quickly and allow the drivers to resume clearing the neighbourhood routes.

Under the old system individual ploughs had cleared the priority routes so it took time to clear two to three lanes in each direction. Now with the trucks working in tandem they quickly clear the major routes and have a shorter return journey to continue clearing the neighbourhood routes.

Every three of four hours, depending on the snow accumulation, the supervisors pull the trucks off the secondary routes to re-clear the priority roads.

Driver feedback was taken into account in finalising how the routes are ploughed and the supervisors remain in their district throughout the storm, monitoring road conditions and the clearance operation. “So the supervisor knows where people park cars and can warn them not to do so when a storm is due otherwise they will get towed. Their priority is clearing the constituency areas because that’s where the complaints come from,” says Nash.

To cut the clearance time the fleet has been enlarged and now includes 29 six wheel and three 10-wheel plough trucks along with 16 small machines to clear 13,1002m (141,00sqft) of sidewalk in the priority areas. All the vehicles and machines are tracked using Hartford’s bespoke system to monitor progress and an additional benefit is that this allows the productivity of individual ploughs and machines to be evaluated.

When large storms hit and the snow has to be physically removed rather than being pushed aside, GIS mapping is used to identify the best locations for areas to deposit the collected snow (known as 'snow farms'). These are typically large open areas with good access such as car parks at locations which minimise the haul distances.

The new system has been in place for three winters, the first of which saw average snowfall but a dramatic reduction in complaints. Both the drivers and supervisors are getting better every year,” says Nash - which was just as well because the second year (2014/15) saw record snowfalls.

“We shone that year because despite the record snowfall, all the roads were open all year round and we did this without using contractors,” he says.

The data collected over that winter provided the justification for the new 10-wheelers to clear the main roads during heavy snow storms using an additional wing-plough (also fitted to one wheel loader). A normal blade is positioned at the front of the vehicle with the additional wing plough to the side which doubles the ploughed width, enabling two lanes to be cleared in a single pass. Other updates are being considered which will let the managers know when the plough blade is in the down position and when the spreader is in operation.

Having logged all the routes for the ploughs and sequenced the sidewalk clearing operations, standard operating procedures have been drawn up for each district and each operator (plough truck driver or sidewalk machine). Different procedures, equipment and staffing levels are deployed depending of the severity of the storm being predicted by the national weather service. The arrangements include deploying equipment, operators and supervisors to their districts before the storm hits to pre-treat the roads.

“Having everything down on paper helps us identify our staff and equipment requirements and we haven’t yet had to hire contractors or employ additional people. We still do call on particular individuals from other departments in the event of a major storm.”

Outside of the winter period the vehicles are used on other duties such as garbage collection and, in the fall, leaf collections and the tracking system is also used to ensure all roads have had a collection.

As to payback, Nash says the allocated $200,000/winter budgeted for using contractors has remain unused for three winters.

Overtime has been reduced in the winter by the more efficient use of the plough operators’ time and throughout the year by being able to check that the vehicles are at their intended destinations at the correct time. If not the supervisors, who tract their vehicles on their cell phones, can make direct contact with the operative to enquire about the nature of the problem.

Other authorities have expressed interest in Hertford’s procedures which Nash welcomes and is happy to accommodate: “Everything I do and have done is paid for by the public. There is nothing proprietary about it and if other authorities can benefit from all or part of this work then I am happy to supply it to them without charge.”

Now that’s something you won’t hear every day.