The use of alcohol interlocks to prevent drink driving and change driver behaviour is gaining ground around the world but needs greater buy-in from authorities as Colin Sowman discovers.

The often repeated mantra says that prevention is better than cure - and none more so than in the case of drink-driving. The introduction of the breathalyser provided an objective indication of alcohol consumption instead of having drivers touch their nose or walk in a straight line.

Initially breathalysers were used as a roadside indicator, with those failing the test subjected to a blood tests – which was the basis of most legislation. As the technology developed and proved reliable, many countries added breath alcohol limits to the legislation. This, for instance, sees England’s blood alcohol limit of 80 milligrams per 100 millilitres joined by 35 micrograms per 100 millilitres of breath (and 107 milligrams per 100 millilitres of urine).

While many would argue that impairment starts at much lower alcohol levels, getting some drivers to comply with existing limits is proving difficult enough. Tough penalties can deter potential offenders - but that only works if the driver thinks they may get caught. If not, the penalties are irrelevant.

This is arguably the situation in many countries where legislation is in place and progress has been made, but where there is still a continuing problem with alcohol-related crashes, injuries and fatalities. Figures from America show that over the last decade alcohol impaired driving fatalities have declined by 27% but still accounted for almost 10,000 fatalities in 2014 – almost one third of its motor vehicle traffic fatalities. That year US enforcement authorities arrested 1.1 million drivers for drink or drug driving offences - and even that represents only 1% of the 121 million self-reported episodes of alcohol-impaired driving recorded each year.

In the UK the problem is at a lower level (around 12% of road fatalities with 220 people killed and 3,200 drivers involved in crashes failing a breath test) but those figures have remained stubbornly constant for the last four years. Many countries have a similar pattern.

As an indication of how entrenched this problem is, there is evidence that up to 70% of drink-drivers will continue to drive while their licence has been suspended and more than one-third of first time drink driving offenders will become recidivists. The volume of drink driving violations and prosecutions not only places a burden on the enforcement agencies and the courts, it shows this approach is not working, so some authorities are turning to behavioural modification to achieve the legislative aim.

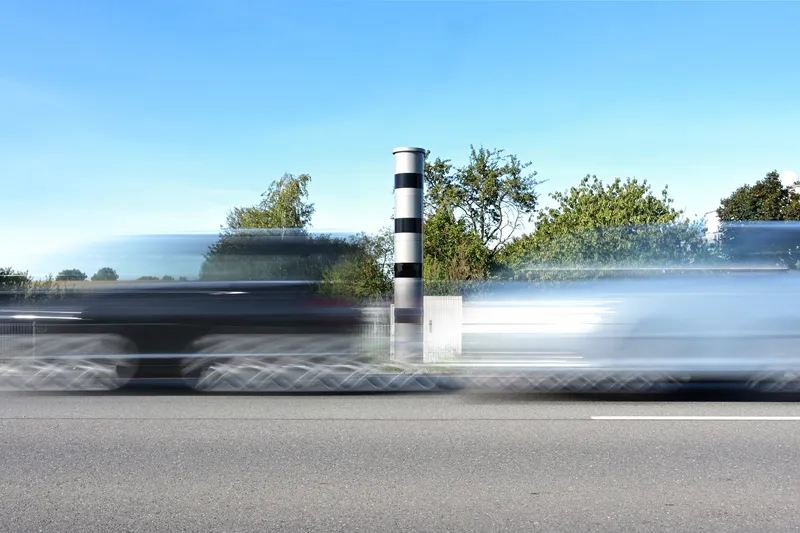

One approach that has proved promising results is the mandatory fitting of alcohol interlocks to offenders’ vehicles which prevent the engine from being started until the driver has blown a negative breath test. That way not only is the driver prevented from committing an offence, they cannot become the hazard to other road users they would otherwise be.

Providers of this technology include US-based companies LifeSaver and

As is usual the implementation varies from one jurisdiction to another with some passing laws requiring the fitting of alcohol interlocks to the vehicles of all those convicted of a drink drive offence. In other countries and states, if the blood alcohol is relatively low and the impaired driver has not caused a crash, the interlock may be offered as an alternative to prosecution.

Ten years ago the Province of Quebec, Canada was one of the first to introduced an alcohol interlock program and this includes the requirement for drivers to demonstrate compliance with program conditions before they can regain an unrestricted licence.

The alcohol interlock program is open to all offenders except those convicted of the most egregious drink driving offences, such as causing injury or death, and is mandatory for repeat offenders. In practice, more than half of those offered the alcohol interlock program agree to participate instead of facing a criminal sanction.

According to the US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), installing ignition interlocks can reduce repeat offences by up to 70%. Most US states have laws that require some or all convicted DWI (driving while impaired) offenders to install ignition interlocks on their vehicle and more than 20 states suspend a driver’s licence if they refuse to have an interlock installed. Yet in practice the take up is low with only about 21% of those arrested for DWI installing interlocks.

To combat this low take up the CDC has produced a guide to Increasing Alcohol Ignition Interlock Use.

This advocates (among other measures) incentives such as reducing the time the driver’s licence is revoked if they have an interlock fitted. This is coupled with harsh penalties for tampering with the device and includes random checks. Education, coordination and data use are also covered.

Examples cited are a doubling of interlock use in New York after its authority started to require fitment for first-time offenders, and a five-fold increase in Wisconsin following the compulsory fitment for repeat and high blood alcohol offenders. Arkansas opted for the incentive route, reducing or eliminating licence suspension periods when interlocks were fitted, which resulted in a 250% increase in their use.

New Zealand has a programme whereby following an initial three month driving ban, the offender can apply for an ‘alcohol interlock licence’ restricting them to driving vehicles fitted with an approved alcohol interlock. The regulations specify that the interlock must not only prevent the vehicle from starting, it must also randomly require the driver to provide a breath sample when the vehicle is in use. All data and readings are recorded and the driver is required to take their vehicle to an approved centre where that data is downloaded.

A year after the interlock is fitted, drivers meeting the criteria can apply for a zero alcohol licence (which lasts for three years) and once approved, the interlock is removed. The driver remains subject to a zero alcohol limit and if they have even one drink before they drive, they can be charged with drink-driving and disqualified.

Elective fitment

Within industries that use professional drivers, some companies are fitting alcohol interlock devices as a deterrent and a preventative measure.While the UK does not use the interlock approach to enforcement, Runcorn, Cheshire-based independent coach company Anthony’s Travel has fitted its 19 vehicles with interlock devices from

Many of the company’s 32 drivers have nights away with tours and are encouraged to socialise with the tour members. England and Scotland have different alcohol limits (35 and 22 micrograms per 100 millilitres of breath respectively), so the potential for confusion and transgression always exists.

Initially Alcolock UK fitted a demonstration unit free of charge for six months with the interlock limit set at nine micrograms per 100 millilitres of breath. This is around a quarter of the limit in England and easily accommodates the lower limits in Scotland.

Richard Thomas, general manager at Alcolock UK, says it is impractical to set a zero limit because products such as mouth wash contain alcohol and will cause a reading – albeit at a low level.

“On the first day,” says Bamber, “two drivers were sent home” but quickly adds, “they weren’t over the legal limit - but they were over our limit.”

Initially some drivers came into the yard on their days off to try the system and check what level of consumption would trigger a ‘fail’. As driving is their livelihood, this was not a particular surprise for Bamber - unlike the reaction from some passengers.

“Quite often passengers would see the driver blowing into this device and ask what they are doing. When the driver told them the coach won’t start unless they provide a suitable sample of breath, the passengers were quite impressed and told others about how we protect our customer’s safety.”

At the end of the six-month trial period the company took the decision to install interlocks in its other passenger vehicles. “In the four years since we installed that initial unit, we’ve never received a call from a driver saying the vehicle wouldn’t start because of the interlock,” says Bamber.